|

What

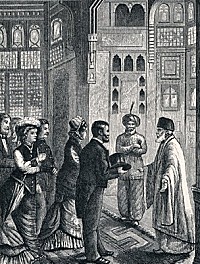

began as a small trickle of American travelers to Egypt in

the early part of the nineteenth century became a steady stream,

rivaling the flow of the Nile, by the first years of the twentieth

century. What

began as a small trickle of American travelers to Egypt in

the early part of the nineteenth century became a steady stream,

rivaling the flow of the Nile, by the first years of the twentieth

century.

By

the late 1860s, Thomas Cook and Son began offering Nile excursions

on steamers and luxurious dhahabîyehs, reducing

much of the hardship of earlier travel. These conveniences

brought more American visitors to Egypt, ranging from noted

public figures to midwestern businessmen and their families.

Soon, the exotic locales of Nubia and the oases of the Western

Sahara Desert were offered as de rigueur stops on the Grand

Tour for American travellers.

In

1867, Samuel Langhorne Clemens in the guise of Mark Twain

made a tour of Europe, Egypt, and the Holy Land and described

them in his book Innocents Abroad (1869). Americans

who later traveled through these same regions liked to retell

Twain's witty anecdotes and observations which they compared

to their own experiences.

A

number of the other Americans who published books based on

their own journeys to Egypt included Lincoln's Secretary of

State William H. Seward and his daughter Olivia (1871); essayist

and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson (1872-1873); industrialist Andrew

Carnegie (1879); journalist Richard Harding Davis (1892);

illustrator Charles Dana Gibson (1897-1898); and writer Henry

Adams (1898).

Among

the other American visitors to Egypt at this time, but with

a much different purpose, were hundreds of Civil War veterans

who joined the army of the Khedive Ismail, serving in his

Ethiopian wars. Among those who wrote accounts of their adventures

were William Wing Loring, Charles Chaillé-Long, and

William Dye. Among

the other American visitors to Egypt at this time, but with

a much different purpose, were hundreds of Civil War veterans

who joined the army of the Khedive Ismail, serving in his

Ethiopian wars. Among those who wrote accounts of their adventures

were William Wing Loring, Charles Chaillé-Long, and

William Dye.

As

the century progressed, travel became easier and the reviewer's

prediction became a reality. Thus, in 1895 we find Agnes Repplier's

(1855-1950) account of "Christmas Shopping in Assuân"

in Atlantic Monthly where she notes, "shopping

on the Nile is a very different matter from shopping on Chestnut

Street or Broadway" (p.681).

By

1908, travel accounts were no longer tales of adventure and

hardship, but the tongue-in-cheek travails described by Lillian

C. Gilpin in "To the Pyramids with a Baby Carriage"

appearing in Harper's Weekly:

The

wheels of the baby's "Desert Schooner" cling

sorrily, so we halt, rig up a sort of awning over the

little one's head by means of a cotton sheet brought for

the purpose, and a couple of maize sticks pulled at the

foot of the great monuments to Time (p.30).

For

some, more bored than awed, this new traveler's Egypt had

lost the sense of wonder earlier travellers found. Travelers

such as the woman quoted in Constance Fenimore Woolson's (1840-1894)

"Cairo in 1890":

I

have spent nine long days on this boat, staring from morning

till night. One cannot stare at a river forever, even

if it is the Nile! Give me a thimble (p.665).

Though

perhaps lacking in the scope and grandeur of European accounts,

the American experience in Egypt has left an important and

fascinating record in a wealth of travel accounts.

As

Woolson later noted, the American experience is still in its

infancy compared to the European nations: As

Woolson later noted, the American experience is still in its

infancy compared to the European nations:

In connection with the pyramids, the English may be said

to have devoted themselves principally to measurements.

The genius of the French, which is ever that of expression,

has invented the one great sentence about them. So far,

the Americans have done nothing by which to distinguish

themselves; but their time will come, perhaps. One fancies

that Edison will have something to do with it (pp.670-71)

In

retrospect, we can now see it was not Edison, but rather the

collected volumes of travel accounts with which Americans

made their mark. |